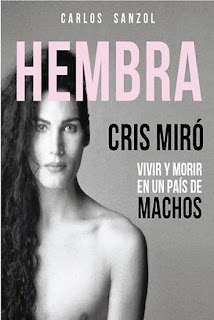

Original title: "Hembra. Cris Miró. Vivir y morir en un país de machos" (Female. Cris Miró. Living and dying in a country of machos) by Carlos Sanzol.

Carlos Sanzol’s book Hembra. Cris Miró. Vivir y morir en un país de machos is a deeply researched and emotionally charged portrait of one of Argentina’s most iconic and misunderstood figures. Published by Milena Caserola, it traces the dazzling rise and tragic fall of Cris Miró, the country’s first transgender vedette, who illuminated Buenos Aires’s theater stages in the 1990s while challenging a culture steeped in machismo and hypocrisy. The author, a journalist and scholar with a background in Social Communication and Journalism, uses his expertise to reconstruct not only the personal story of a woman who dared to exist authentically but also the collective history of a society struggling with its own identity.

Cris Miró’s life is the central thread in a tapestry woven with contradictions. She was both adored and condemned, celebrated and judged. Her story begins in Belgrano, Buenos Aires, where she was born on September 16, 1965. From an early age, she stood out for her femininity, her attraction to the world of performance, and her instinctive rejection of traditional gender roles. Sanzol recounts how her father and brother struggled to understand her, while her mother became her first ally. This early domestic tension mirrored the conflict that would later define her public life: a permanent negotiation between visibility and rejection, admiration and exclusion.

Miró’s artistic journey began in the alternative theater scene, under the guidance of Jorgelina Belardo and Juanito Belmonte. Her performances in avant-garde productions such as Fragmentos del infierno and Orgasmo apocalíptico were bold explorations of sexuality and identity at a time when Argentina still criminalized nonconforming gender expressions. Her transition to mainstream fame came in 1995 when she joined the legendary Teatro Maipo as a vedette in Viva la revista. It was a historic moment. The revue stage, traditionally the exclusive territory of cisgender women, suddenly featured a trans performer who not only captivated audiences but redefined the concept of sensuality in the public imagination.

Sanzol’s narrative captures the contradictions of this moment with great sensitivity. Miró’s success, he argues, revealed the double standard that governed Argentina’s moral landscape. Audiences paid to see her perform under the dazzling lights of the theater, yet the same society allowed police to arrest other trans women under the so-called “Escándalo” edict simply for dressing as women in public. The body of Cris Miró became, in Sanzol’s words, a mirror of national hypocrisy. It reflected a country that pretended to have entered modernity while remaining chained to the patriarchal codes of the past.

The author situates Miró’s fame within the broader context of 1990s Argentina, a period of neoliberal dreams and deep social inequality. The country was trying to reinvent itself under the illusion of belonging to the “first world,” while corruption, unemployment, and exclusion eroded the lives of those on the margins. In this fractured society, Cris Miró emerged as both a symbol of aspiration and a reminder of the realities that most preferred to ignore. Sanzol writes that Argentina itself was “a nation that, like Cris, tried to find its identity in a distorted mirror.” Her glamorous image coexisted with the moral decay and impunity of a masculine system that rewarded power and punished difference.

Through interviews, archival materials, and press coverage, Sanzol reconstructs how the media alternated between fascination and cruelty. When Miró appeared on Mirtha Legrand’s television program, she faced invasive questions about her gender and past, reflecting the voyeuristic curiosity that surrounded her. Yet, despite such treatment, she maintained remarkable composure and dignity. Her public statements revealed a lucid understanding of her identity. “I was born with a certain sex, which means I have documents with a male name and gender,” she said, “but what matters most is what I feel. I am one person, and that is what’s important.” These words, simple and profound, summarize her philosophy of self-acceptance and authenticity.

Sanzol also examines how Miró’s relationship with the trans community was complex. While she opened doors for future generations, some activists criticized her for not openly engaging in political struggles or for embodying the idealized femininity demanded by patriarchy. Yet her mere presence on stage was, in itself, a revolutionary act. She brought transgender visibility into the mainstream, humanizing a community that until then had been confined to the shadows of society. Her success paved the way for artists like Flor de la V, who would later describe her as “a star that shone for too short a time but continues to light the path forever.”

The final chapters of Hembra deal with Miró’s illness and death with a balance of compassion and journalistic rigor. In 1999, weakened by lymphoma and complications related to HIV, she was hospitalized at the Santa Isabel clinic in Buenos Aires, where she died on June 1 at the age of 33. The reaction to her passing revealed the entrenched prejudices of the era. Newspapers and talk shows often treated her death as a spectacle, while the LGBTQ+ organization Comunidad Homosexual Argentina rightly pointed out that she had suffered from the most lethal disease of all: discrimination.

Beyond recounting her biography, Sanzol uses Cris Miró’s story to explore the anatomy of Argentine machismo. He describes how she became both a beneficiary and a victim of that system: a beneficiary because she embodied the sensual ideal that men desired, and a victim because that same system refused to accept her as a legitimate woman. In Miró’s life, the contradictions of a patriarchal culture found their most visible expression. Her beauty and talent seduced the public, but her identity challenged its comfort zones.

The book also highlights how, after her death, her image continued to grow in significance. She became a posthumous icon of the 1990s, representing both the glamour and the pain of a generation. Today her portrait hangs in the Casa Rosada Museum as part of the exhibition Íconos Argentinos, alongside other figures who shaped national identity. Her influence echoes in literature, as in Camila Sosa Villada’s novel Las malas, where trans women mourn her as “the Evita of the travestis,” and in the audiovisual field, with the recent television series Cris Miró (Ella) bringing her story to new audiences.

In Hembra. Cris Miró. Vivir y morir en un país de machos, Carlos Sanzol offers more than a biography. He presents a reflection on visibility, desire, and the contradictions of an entire nation. His writing avoids sensationalism and focuses instead on the complexity of a woman who lived between acceptance and rejection, who conquered the stage only to be destroyed by a society that never fully embraced her. Through Miró’s story, Sanzol invites readers to question what it means to be a woman, an artist, and a symbol in a culture dominated by men. The book is, ultimately, a tribute to courage and fragility, to the human need to be seen and loved for who one truly is.

Available via lacapitalmdp.com

Photos: - La Nación and Archivo de la Memoria Trans

Post a Comment